UN: Growth of World Law.

UN: Growth of World Law.

Genocide Convention: 9 December 1948.

Featured Image: Photo by Pixabay on Pexels

By Dr. Rene Wadlow.

Genocide Convention: 9 December 1948.

An Unused but not Forgotten Standard of World Law.

Genocide is the most extreme consequence of racial discrimination and ethnic hatred. Genocide has as its aim the destruction, wholly or in part, of a national, ethnic, racial or religious group as such. The term was proposed by the legal scholar Raphael Lemkin, drawing on the Greek genos (people or tribe) and the Latin cide (to kill).(1) The policies and war crimes of the Nazi German government were foremost on the minds of those who drafted the Genocide Convention, but the policy was not limited to the Nazi. (2)

The Genocide Convention is a landmark in the efforts to develop a system of universally accepted standards which promote an equitable world order for all members of the human family to live in dignity. Four articles are at the heart of this Convention and are here quoted in full to understand the process of implementation proposed by the Association of World Citizens, especially of the need for an improved early warning system.

Article I

In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Unlike most humanitarian international law which sets out standards but does not establish punishment, Article III sets out that the following acts shall be punishable:

- (a) Genocide;

- (b) Conspiracy to commit genocide;

- (c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

- (d) Attempt to commit genocide;

- (e) Complicity in genocide.

Article IV

Persons committing genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be punished, whether they are constitutionally responsible rulers, public officials or private individuals.

Article VIII

Any Contracting Party may call upon the competent organs of the United Nations to take such action under the Charter of the United Nations as they consider appropriate for the prevention and suppression of acts of genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III.

Numerous reports have reached the Secretariat of the United Nations of actual, or potential, situations of genocide: mass killings; cases of slavery and slavery-like practices, in many instances with a strong racial, ethnic and religious connotation – with children as the main victims, in the sense of article II (b) and (c). Despite factual evidence of these genocides and mass killings as in Sudan, the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, Burundi, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sierra Leone and in other places, no Contracting Party to the Genocide Convention has called for any action under article VIII of the Convention.

As Mr Nicodene Ruhashyankiko of the Sub-Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities wrote in his study of proposed mechanisms for the study of information on genocide and genocidal practices “A number of allegations of genocide have been made since the adoption of the 1948 Convention. In the absence of a prompt investigation of these allegations by an impartial body, it has not been possible to determine whether they were well-founded. Either they have given rise to sterile controversy or, because of the political circumstances, nothing further has been heard about them.”

Yet the need for speedy preventive measures has been repeatedly underlined by United Nations Officials. On 8 December 1998, in his address at UNESCO, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan said:

“Many thought, no doubt, that the horrors of the Second World War – the camps, the cruelty, the exterminations, the Holocaust – could not happen again. And yet they have, in Cambodia, in Bosnia and Herzegovina, In Rwanda. Our time – this decade even – has shown us that man’s capacity for evil knows no limits. Genocide – the destruction of an entire people on the basis of ethnic or national origins – is now a word of our time, too, a stark and haunting reminder of why our vigilance must be eternal.”

In her address Translating words into action to the UN General Assembly on 10 December 1998, the then High Commissioner for Human Rights, Mrs Mary Robinson, declared :

” The international community’s record in responding to, let alone preventing, gross human rights abuses does not give grounds for encouragement. Genocide is the most flagrant abuse of human rights imaginable. Genocide was vivid in the minds of those who framed the Universal Declaration, working as they did in the aftermath of the Second World War. The slogan then was ‘never again’. Yet genocide and mass killing have happened again – and have happened before the eyes of us all – in Rwanda, Cambodia, the former Yugoslavia and other parts of the globe.”

We need to heed the early warning signs of genocide. Officially-directed massacres of civilians of whatever numbers cannot be tolerated, for the organizers of genocide must not believe that more widespread killing will be ignored. Yet killing is not the only warning sign. The Convention drafters, recalling the radio addresses of Hitler and the constant flow of words and images, set out as punishable acts “direct and public incitement to commit genocide”.

The Genocide Convention

The Genocide Convention, in its provisions concerning public incitement, sets the limits of political discourse. It is well documented that public incitement – whether by Governments or certain non-governmental actors, including political movements – to discriminate against, to separate forcibly, to deport or physically eliminate large categories of the population of a given State, or the population of a State in its entirety, just because they belong to certain racial, ethnic or religious groups, sooner or later leads to war. It is also evident that, at the present time, in a globalized world, even local conflicts have a direct impact on international peace and security in general.

Therefore, the Genocide Convention is also a constant reminder of the need to moderate political discourse, especially constant and repeated accusations against a religious, ethnic and social category of persons. Had this been done in Rwanda, with regard to the radio Mille Collines, perhaps that premeditated and announced genocide could have been avoided or mitigated.

For the United Nations to be effective in the prevention of genocide, there needs to be an authoritative body which can investigate and monitor a situation well in advance of the outbreak of violence. As has been noted, any Party to the Genocide Convention (and most States are Parties) can bring evidence to the UN Security Council, but none has. In the light of repeated failures and due to pressure from non-governmental organizations, the Secretary-General has named an individual advisor on genocide to the UN Secretariat. However, he is one advisor among many, and there is no public access to the information that he may receive.

Direct and public incitement to commit genocide.

Therefore, a relevant existing body must be strengthened to be able to deal with the first signs of tensions, especially ‘direct and public incitement to commit genocide.” The Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) created to monitor the 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination would be the appropriate body to strengthen, especially by increasing its resources and the number of UN Secretariat members which service the CERD. Through its urgent procedures mechanisms, CERD has the possibility of taking early-warning measures aimed at preventing existing strife from escalating into conflicts, and to respond to problems requiring immediate attention. A stronger CERD more able to investigate fully situations should mark the world’s commitment to the high standards of world law set out in the Genocide Convention.

Notes

1) Raphael Lemkin. Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (Washington: Carnegie Endowment for World Peace, 1944).

2) For a good overview see: Samantha Power. A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide (New York: Basic Books, 2002)

3) E/CN.4/Sub.2/1778/416 Para 614

President, Association of World Citizens (AWC).

Estudied International relations in The University of Chicago.

Estudied Special Program in European Civilization en Princeton University

Here are other publications that may be of interest to you.

Kenneth Waltz: The Passing of the Second Generation of the Realists.

The death of Professor Kenneth Waltz; on 12 May 2013 in New York City; at the age of 88; marks the start of the passing of the second generation of…

Benjamin Ferencz, Champion of World Law, Leave a Strong Heritage on Which To Build.

Featured Image: Prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz at the Einsatzgruppen Trial in Nuremberg. Ferencz was a civilian employee with the OCCWC, thus the picture showing him in civilian clothes. The Einsatzgruppen Trial (or „United…

Bronislaw Malinowski: Understanding Cultures and Cultural Change.

Featured Image: Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942), Professor of Anthropology. By Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons. Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) whose birth anniversary…

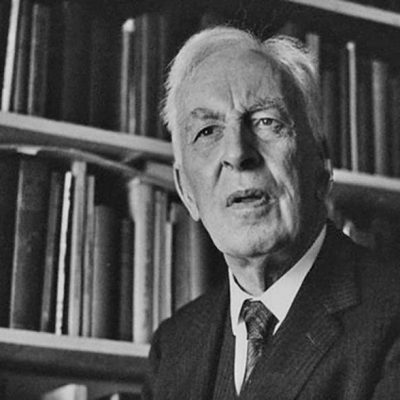

Arnold Toynbee: A World Citizens view of challenge and response.

Featured Image: Arnold Toynbee. By Atyyahesir, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975) was a historian, a philosopher of history, and an advisor on the wider Middle…