Portraits of World Citizens.

Portraits of World Citizens.

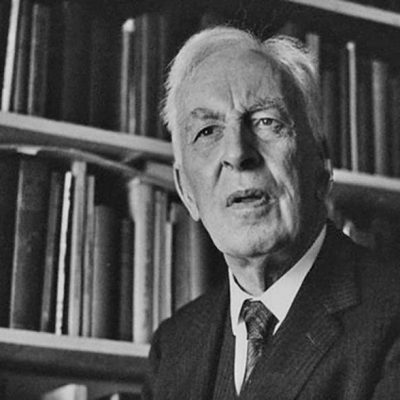

Carl G. Jung: The Integration of Opposites.

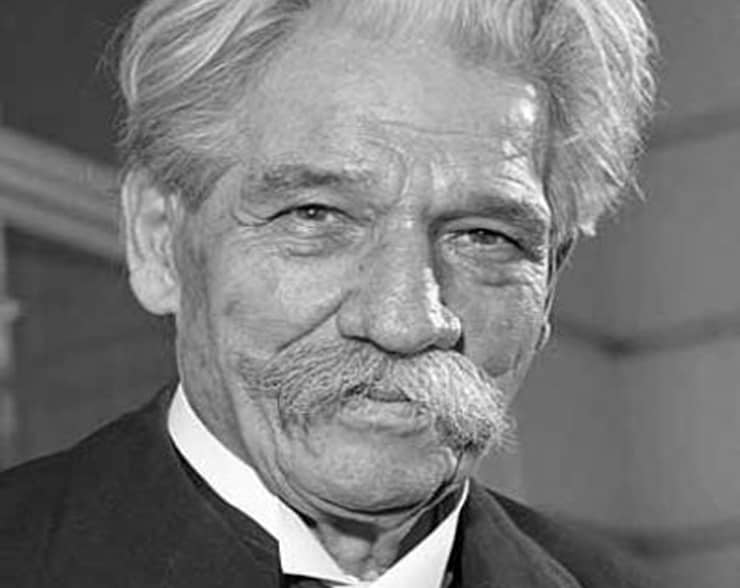

Carl.G. Jung (26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was born in Kesswil on the Lake of Constance; where the three countries that most influenced him met: Switzerland, Austria, and Germany. German-speaking Switzerland was his roots; his grandfather having been the Rector of the University of Basle and a well-known medical doctor; Austria, Vienna in particular; the home of Sigmund Freud whose thought and psycological practice he championed before taking his distance; Germany whose Nazi ideology he tried to understand through his psychoanalytical tools.

Moreover; family lore stated that the grandfather was the illegitimate grandson of Goethe; making Jung’s ties to German philosophy, especially an early interest in the Zarathustra of Nietzsche, all the stronger.

Colorized painting of Sigmund Freud. By Photocolorization, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Erich Fromm: Meeting the Challenges of the Century.

Also sprach Zarathustra. Ein Buch für Alle und Keinen. In drei Theilen. By Unknown authorUnknown author, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Alexandre Marc: Con-federalism, Cultural Renewal and Trans-frontier Cooperation.

Book Aion.

Jung combined an interest in German thought; especially the writings of early German alchemists with a deep interest in Chinese Taoist philosophy; the two currents are brought together in his 1951 book Aion. In Aion, he deals directly with the passage of the Piscean Period to the Age of Aquarius. He analyses astrological imagery embodied in Zodiacal ages in order to deal with the psychological problems of this period of transition.

The astrological sign of Pisces is often represented as two fish − one light, the other dark in color − swimming in opposite directions. The Age of Pisces; which started roughly at the same time as the birth of Jesus is the period in which Christianity developed and became the normative spiritual influence for much of the world.

The Piscean Period; true to its image of the fish going in opposite directions, has been one in which the dominant ideologies have been of opposing dualism: the kingdom of the saved and the world of the damned in Christianity, the dar al-Islam and the dar al-harb (the house of Islam and the house of war) in Islam, the antagonist socialist and capitalist worlds in Marxist thought.

Co-Existence.

The chief psychological as well as political problem of the Piscean Period was how to prevent one of the dualities from destroying the other − how to keep a balance of power.

None of the dominant ideologies contained the key to a creative balance between opposites; although in the late Cold War period (1970s-1980s); the idea of “co-existence” was developed by thinkers on the edges of political power in East and West. Co-existence implied a relationship among groups in which none of the parties is trying to destroy another. Co-existence provided a starting point for succeeding generations to reframe their understanding of the enemy without necessarily abandoning other political or cultural principles.

However; co-existence is much less than the Taoist concept of equilibrium; of a balance between forces which would create greater harmony and wealth of being. Thus; Jung looked to Chinese Taoism for that integration of the principles and energies of yin;

(the receptive and feminine) and yang (the active and masculine). The Tao is the ground of being; the void from which all arises. As Lao Tzu in the Tao Te Ching notes:

“The Tao is like a well,

Used but never used up.

It is like the eternal void

Filled with infinite possibilities.”

In another verse Lao Tzu writes:

“The Tao is called the Great Mother:

Empty yet inexhaustible,

It gives birth to infinite worlds.”

In the infinite world of created things; the Tao is most often represented as the harmonious balance between yin and yang. Lao Tzu noted :

“Of the energies of the universe, none is greater than harmony. Harmony means the regulation of yin and yang.”

Jung became interested in Taoism by meeting in 1922 Richard Wilhelm; a German missionary to China; who had become very interested in Taoism. Jung viewed Wilhelm and his work as creating a bridge between East and West. Wilhelm was the messenger from China who was able to express profound things in plain language which disclose something of the simplicity of great truth and deep meaning. Richard Wilhelm had translated a Taoist healing text; The Secret of the Golden Flower to which Jung wrote a psychological commentary published in 1929. Wilhelm had also produced a translation of Lao Tzu’s Tao Te Ching; as well as the I Ching (The Book of Changes) − a widely used book of Chinese divination, some of which predates the rise of Taoism in the 6th century BC.

The Chinese Taoists were directly concerned with mental health and healing, and there were contemporary healers which Wilhelm had met. The Taoist balance between what could be considered at one level as opposites was close to Jung’s psychoanalytical efforts where he contrasted the introvert and the extrovert, thought and feeling, the person and the shadow, the conscious and the unconscious. The essential task of Jung’s psychology is to help in the process of “individuation” − a process toward wholeness, which like Taoism, is characterized by accepting and transcending opposites.

As Jung noted, Taoist thought would play an increasingly powerful role in the transition between the Piscean Period and the Age of Aquarius.

“The spirit of the East is really at our gates. Therefore it seems to me that the search for Tao, for a meaning in life, has already become a collective phenomenon among us, and to a far greater extent than is generally realized.”

As Lao Tzu wrote:

“Let the Tao be present in your life

Rene Wadlow, President and a representative to the United Nations, Geneva, Association of World Citizens.

President, Association of World Citizens (AWC).

Estudied International relations in The University of Chicago.

Estudied Special Program in European Civilization en Princeton University

Here are other publications that may be of interest to you.

Kenneth Waltz: The Passing of the Second Generation of the Realists.

The death of Professor Kenneth Waltz; on 12 May 2013 in New York City; at the age of 88; marks the start of the passing of the second generation of…

Benjamin Ferencz, Champion of World Law, Leave a Strong Heritage on Which To Build.

Featured Image: Prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz at the Einsatzgruppen Trial in Nuremberg. Ferencz was a civilian employee with the OCCWC, thus the picture showing him in civilian clothes. The Einsatzgruppen Trial (or „United…

Bronislaw Malinowski: Understanding Cultures and Cultural Change.

Featured Image: Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942), Professor of Anthropology. By Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons. Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) whose birth anniversary…

Arnold Toynbee: A World Citizens view of challenge and response.

Featured Image: Arnold Toynbee. By Atyyahesir, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975) was a historian, a philosopher of history, and an advisor on the wider Middle…