Rapprochement of Cultures.

Rapprochement of Cultures.

Hermann Hesse: Revolt and Enlightenment.

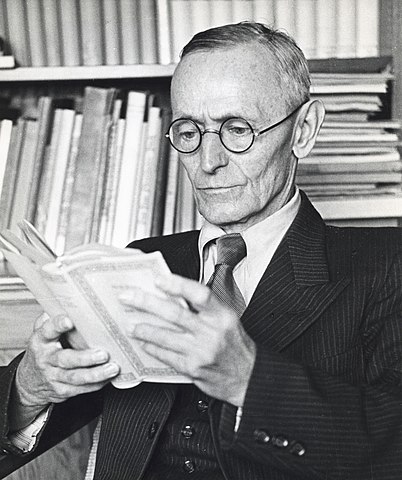

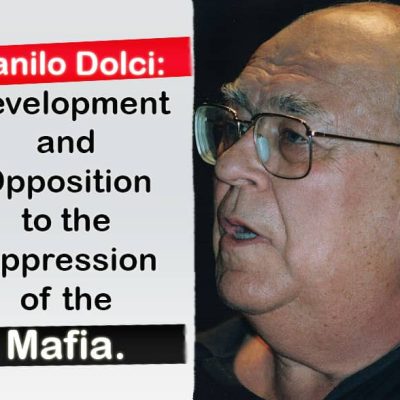

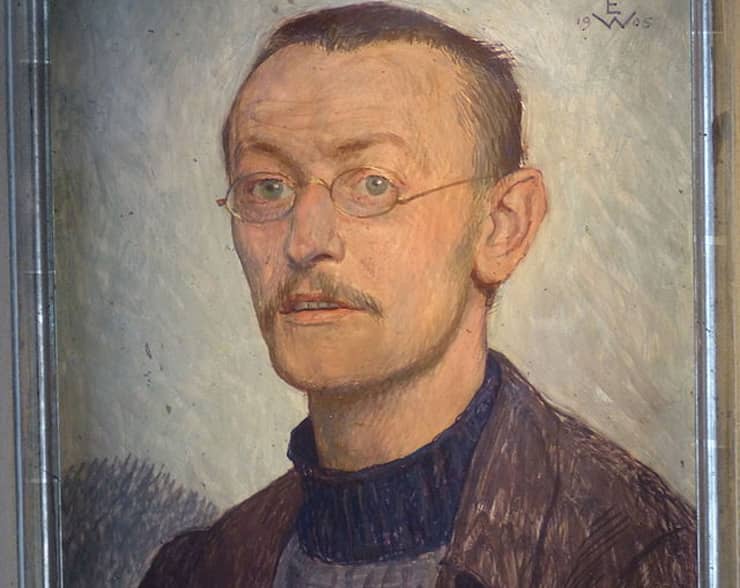

Featured Picture: Gaienhofen (Baden-Württemberg). Hermann Hesse House – Portrait (1905) of Hermann Hesse by Ernst Würtenberger. By Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Hermann Hesse (1877-1962); whose birth anniversary we mark on 2 July; was born into a German Protestant missionary family which had worked particularly in India. His mother was born in India; and his maternal grandfather had translated Christian scriptures into Indian languages; and later in his life developed a German- Indian languages dictionary. His father had also been a Protestant missionary in India; but by the time Hermann Hesse was born in 1877; had returned to Germany to the Black Forest area; where he founded a small publishing house to publish Protestant books. Hermann’s father thought that he should follow the pattern of both sides of his family; become a Protestant minister and perhaps go and preach in Asia.

However; in a theme which he takes up in his main novels; he revolted early against family authority, and so his father sent him away to a boarding school. In fact; he went to several different boarding schools; where he remained in revolt against school authority. He finally finished secondary school and started university. However German universities of his time were as authority-bound as were secondary schools; and he quickly dropped out.

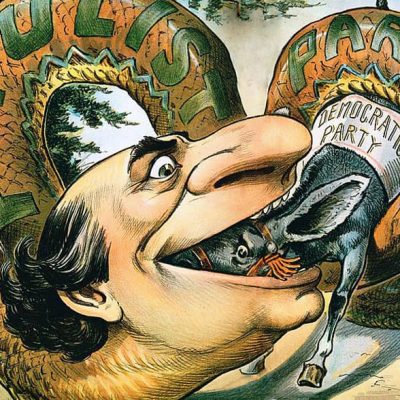

A viper nourished at the breast of an unsuspecting audience.

Hermann Hesse first thought of becoming a painter; and then decided to be a novelist while earning his living in odd jobs; his father having cut off all financial support. In the years prior to the First World War; he wrote a number of novels in the romantic style of the time. Hermann Hesse started to earn money from his writing and editing. In 1911; he went to India but not to convert Indians to Christianity, but to learn about Hinduism, Buddhism, and Chinese philosophy. Hesse’s Indian experience set the stage for his awareness that true freedom must be an inner one.

The outbreak of the First World War had a heavy negative impact on Hermann Hesse; a pacifist who believed that an avenue to peace was to build bridges between cultures. As he was already living in Bern, Switzerland, he refused to return to Germany for war service. He lost his earlier popularity among German readers who were, for the most part, caught up in the war spirit. Hermann Hessse was denounced in the press as”a viper nourished at the breast of an unsuspecting audience.” By 1916, his marriage and family fell apart, and he was under great mental strain, his wife confined to a mental institution and his son seriously ill.

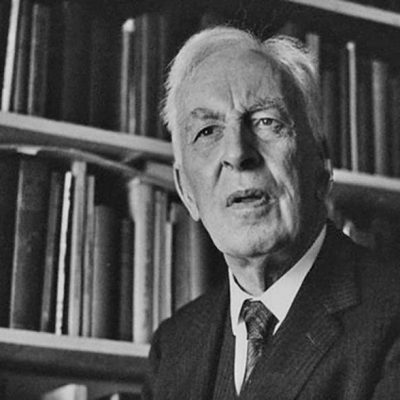

Hermann Hesse by Unknown authorUnknown author, CC BY-SA 3.0 NL <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/nl/deed.en>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Demian and Siddhartha.

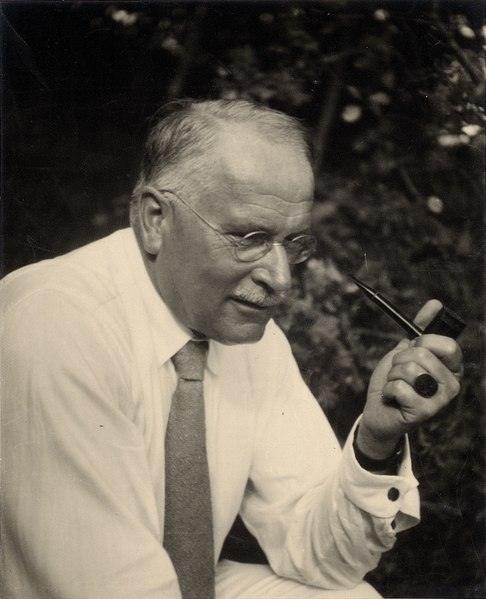

Thus, in 1916-1917 he undertook a psychoanalysis supervised by C.G. Jung. Through Jungian psychoanalysis he developed the idea of a correspondence between an inner state of being and its expression in the outer world. The war was not only raging on the battlefield but also within the spirit of a generation whose values had collapsed. Hermann Hesse wrote Demian in 1917. His hero says:

“The world wants to renew itself. There is a smell of death in the air. Nothing can be born without first dying”.

Demian dies on a Flanders battlefield unable to develop a new system of values. The book was taken up by youth in the years following the end of the war when many came to wonder if the outcome was worth the sacrifices.

Rebellion against established structures, the quest for personal values and a religious impulse are all elements in Siddhartha, published in 1922, perhaps his most widely-read book. Hesse reworks the early quest of the Buddha into a life-long process. In the novel, Siddhartha, son of a Brahman, has been brought up a faithful observer of his father’s religion. At 18, deciding that he cannot find true fulfillment in conventional Hinduism, he sets out in search of an even more austere religion. Three years of asceticism brings him to the realization that extreme and exclusive concentration on the spirit cuts him off from the world of nature and thus takes him even further from the harmony he seeks.

The Glass Bead Game.

In a reversal, he devotes himself for 20 years to a life of the senses, becoming a successful merchant and finding sensual love. However, he understands that a life of matter has brought him no closer to tranquility. Thus he abandons his wife and his possessions. He spends 20 years as a ferryman on a river. He listens to the whisperings of the water and in the company of a sage, he achieves a harmony of being. As Hesse writes “From that hour, Siddhartha ceased to fight against his destiny. There shone on his face the serenity of knowledge of one who is no longer confronted with the conflict of desires, who has found salvation, who is in harmony with the stream of events, with the stream of life, full of sympathy and compassion, surrendering himself to the stream, belonging to the unity of all things.”

It is not clear that Hesse found the harmony of enlightenment in his own life. In his last major work The Glass Bead Game (1943) he describes what might be an ideal Buddhist monastery devoted to the discovery, preservation and dissemination of knowledge. The chief monk leaves and goes out into the world where he quickly dies. Hesse stresses his faith in a society that treasures the traditions and culture of the past while remaining open to the future. This is the Middle Way, the core value of the Buddhist view of Enlightenment.

Statue of Hermann Hesse. By Michael Ney (Sensory Image), Attribution, via Wikimedia Commons.

Rene Wadlow, President, Association of World Citizens.

President, Association of World Citizens (AWC).

Estudied International relations in The University of Chicago.

Estudied Special Program in European Civilization en Princeton University

Here are other publications that may be of interest to you.

Kenneth Waltz: The Passing of the Second Generation of the Realists.

The death of Professor Kenneth Waltz; on 12 May 2013 in New York City; at the age of 88; marks the start of the passing of the second generation of…

Benjamin Ferencz, Champion of World Law, Leave a Strong Heritage on Which To Build.

Featured Image: Prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz at the Einsatzgruppen Trial in Nuremberg. Ferencz was a civilian employee with the OCCWC, thus the picture showing him in civilian clothes. The Einsatzgruppen Trial (or „United…

Bronislaw Malinowski: Understanding Cultures and Cultural Change.

Featured Image: Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942), Professor of Anthropology. By Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons. Bronislaw Malinowski (1884-1942) whose birth anniversary…

Arnold Toynbee: A World Citizens view of challenge and response.

Featured Image: Arnold Toynbee. By Atyyahesir, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975) was a historian, a philosopher of history, and an advisor on the wider Middle…