Portraits of World Citizens.

Portraits of World Citizens.

Salvador De Madariaga: Conscience of the League of Nations.

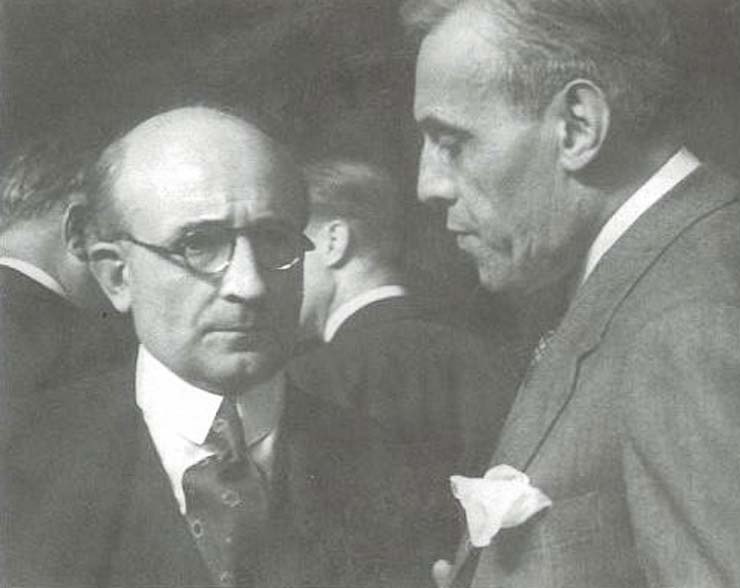

Featured Image: The Spanish writer Salvador de Madariaga and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Argentina José María Cantilo talk during a session of the League of Nations (1936).

By Dr. Rene Wadlow.

The first two organizations using world citizen in its title «World Citizens Association» date from 1939, the eve of the Second World War when the dangers of aggressive nationalism became evident. Both organizations, one in the USA, the other in England, owe much to two friends who had worked together in the League of Nations: Henri Bonnet, a Frenchman living in 1939 in the USA and the better known Salvador De Madariaga of Spain living in England after General Franco came to power in Spain.

Salvador De Madariaga (1886-1978) was called, half ironically, half seriously, ‘the conscience of the League of Nations’; by Sir John Simon, the chief UK delegate to the League of Nations Council and Foreign Secretary. De Madariaga was chairing the Council at the time of the Japanese attack on Manchuria, and he was convinced that this attack, the first major violation of the Covenant by a Council member, Japan, was a key test for the League. He later chaired the League efforts to deal with this Manchurian crisis, as he did with the League efforts to deal with the Italian attack on Ethiopia (Abyssinia, as it was then called).

Salvador De Madariaga had a free hand as chief delegate of Spain during the Republican years (1931-1936); before the Civil War and General Franco‘s victory ended Spanish influence in the League. Spain was not considered a ‘Great Power’; it was not a permanent member of the League Council, but it was large enough and had friends in South America (Spanish America as De Madariaga calls it), so that Spain was often chosen to lead League efforts when a ‘neutral’ state was needed.

Morning Without Noon.

From the memoirs of De Madariaga, Morning Without Noon (London: Saxon House, 1974) written when he was 80 and recalling the period from 1921 to 1936; one gets a good view of the inner workings and the spirit of the League of Nations. They are memories rather than documented research as most of his personal papers were destroyed when Franco took control of Madrid; where De Madariaga had a house and office. Nevertheless, they are a vivid picture of the period and the early functioning of a world institution of which the UN is the continuation in the same buildings. The main League of Nations building for most of its Geneva history is now the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, and the Palais des Nations, finished just as the League was ending its life, is now the UN’s main European headquarters.

Salvador De Madariaga had a first-hand knowledge of the League, having joined its Secretariat in 1921 when it was being created as the first world civil service by Sir Eric Drummond and Jean Monnet. De Madariaga come from a distinguished Spanish family. His father was a military officer who believed that Spain had lost the Spanish-American war to the USA because of a lack of technology. Thus he encouraged his son to have an international technical education, and Salvador De Madariaga went to the elite Ecole Politecnique and the Ecole des Mines, both in Paris and ended with an mining degree which he never used.

However, it gave him a certain image of having technical knowledge and so he was chosen to head the Disarmament Department of the League in 1922 as some people mistakingly thought disarmament was a technical problem. As De Madariaga argues in his book Disarmament (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1929) written just after leaving the League Secretariat:

» disarmament is an irrelevant issue; the true issue being the organization of the government of the world on a co-operative basis.»

De Madariaga left the League Secretariat in 1928, largely because the League had accepted to fire Bernardo Attolico as Under Secretary-General and replace him by Paulucci di Calvoli Barone, a chief assistant of B. Mussolini. There were always persons from the Great Powers in influential League posts; but they were usually intellectuals who believed in the values of the League and not national civil servants. De Madariaga had met Mussolini twice in Rome during disarmament talks. It was De Madariaga’s habit of making quick instinctive judgements of people, and he did not like Mussolini from the start.

De Madariaga became a ‘premature’ anti-Fascist. The fact that the League would place a Fascist civil servant in a key position was for De Madariaga a step backward for a real world civil service. As he writes:

«Here began the downfall of the Secretariat. The Fascist Under-secretary’s room became a kind of Italian Embassy at the League (Save that the Ambassador’s salary was paid by the League), linked directly with Mussolini and openly accepting orders and instructions from him. Paulucci in himself an attractive and friendly person, was nevertheless zealous enough to go about even during official League gatherings sporting the Fascist badge on his lapel.»

As luck would have it, just as he was thinking about leaving the League Secretariat, Oxford University was looking for a professor of Spanish literature for a newly-created chair. Although he had never taught, through League friends, he was named Alfonso XIII Professor of Spanish Studies at Oxford. Once when asked when he had studied Spanish literature, he replied:

«I didn’t need it before, so I shall study it now in order to teach it.»

He held this chair until King Alfonso XIII, who had nothing to do with the chair, was pushed from power.

In 1931 the Spanish Republic was born. The new Spanish Republic leaders, divided among themselves along political lines, were united in wanting the Republic to be represented by intellectuals so that they could explain the aims and values of the Republic. De Madariaga was named Ambassador to France but also asked to represent Spain at the League of Nations since League duties were not considered as a ‘full time job’, and he had League Secretariat experience.

Thus De Madariaga returned to Geneva, one of the few government delegates who knew the workings of the League Secretariat. De Madariaga, when he had been in the Secretariat, because he spoke Spanish, English, and French and was an excellent speaker, had become the chief ‘lay preacher’ for the League and had travelled throughout Europe and the USA giving talks to present the work and the ideals of the League.

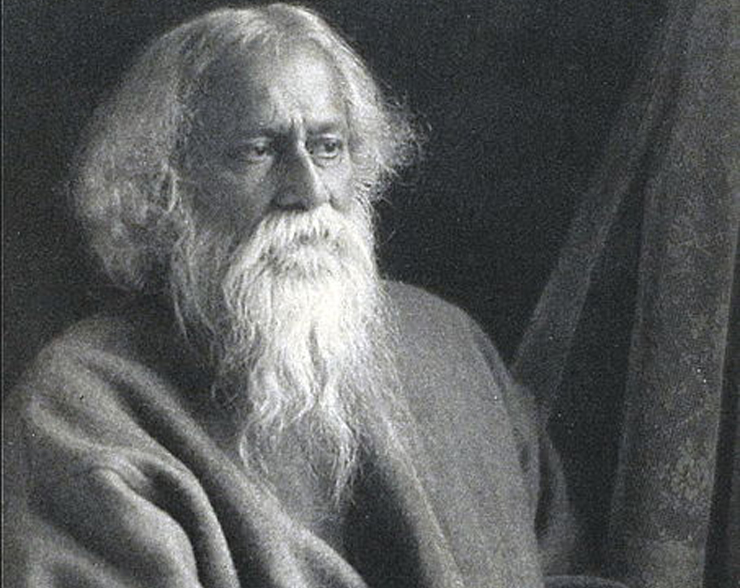

Geneva was a smaller city at the time and much of the intellectual life related to the League. The League had created the Committee for Intellectual Co-operation as an effort to build an intellectual network of support for the League. De Madariaga gives interesting pen portraits of people he had met in the League effort of intellectual cooperation: Paul Valery, R. Tagore, Albert Einstein, Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells and others. Knowing leading intellectuals also opened doors to political figures in many countries. De Madariaga’s knowledge of a country’s politics went beyond his contacts with the delegates to the League.

You might interest read: Rabindranath Tagore: The Call of the Universal Real.

Crisis Situations.

The highlights of De Madariaga’s League efforts were the complicated entry into League membership of Mexico which had been barred by Woodrow Wilson who had bad memories of the Mexican Revolution. Although the USA was not a League member, Mexico had been barred by an annex to the Covenant. De Madariaga had to work so that Mexico would accept League membership without asking for it – such is the craft of diplomacy!.

His two most crucial roles were the League efforts at the time of the Japanese attack on Manchuria and the Italian attack on Ethiopia. His detailed accounts merit reading as to the difficulties of multilateral responses to crisis situations.

De Madariaga resigned as Spain’s chief delegate to the League as the Republic disintegrated, and Franco took power. From 1936 on, he lived outside of Spain, mostly in England and Switzerland and only returned to Spain to visit after the death of Franco. He devoted himself to countering those forces of aggressive nationalism which had destroyed the effectiveness of the League. As he wrote:

«If peace and the spirit of Europe are to remain alive, we shall need more world citizens and more Europeans such as I tried to be.»

De Madariaga encouraged Henri Bonnet, who had been the League Secretariat member in charge of the Committee for Intellectual Co-operation and who was then living in the USA to create in 1939 the World Citizens Association which he did with the young lawyer Adlai Stevenson and Quincy Wright, a leading professor of international relations at the University of Chicago.

De Madariaga helped to create a World Citizens Association in London, also in 1939 – both efforts were too late to block the tide of war. After the Second World War, De Madariaga helped create the College d’Europe in Bruges as a training field for Europeans, especially for those thinking of working in European institutions.

You might interest read: Quincy Wright: A World Citizen’s Approach to International Relations.

Special Program in European Civilization.

He continued his literary and historical interests, writing especially on the founders of ‘Spanish America’. He did some teaching, and in 1955 spent a year at Princeton University in the USA where a new «Special Program in European Civilization» had just been created. His lectures covered the literary analysis of his Portrait de l’Europe (Paris: Calmann-Levy, 1952). As his student that year, I was also interested in disarmament and the functioning of the League of Nations so we had many interesting talks. His was a witty and perceptive mind.

Presidente, Asociación de World Citizens (AWC).

Cursó Estudios de Relaciones Internacionales en La Universidad de Chicago.

Cursó Estudios en el Programa Especial de Civilización Europea en

La Universidad de Princeton

Here are other publications that may be of interest to you.

Sorry, no posts were found.